An interdisciplinary team of researchers at Cornell University is developing a method to 3D-print concrete underwater, an approach that could change how maritime infrastructure is constructed and repaired, according to a university media release.

Led by Sriramya Nair, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Cornell’s David A. Duffield College of Engineering, the project aims to enable on-site underwater construction with minimal disruption to marine environments.

“We want to be constructing without being disruptive,” Nair said, adding that remotely operated underwater vehicles could allow structures to be built “with minimal disturbance to the ocean.”

The work began in response to a 2024 call for proposals from the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which challenged teams to design 3D-printable concrete that could be deposited several metres underwater within a year.

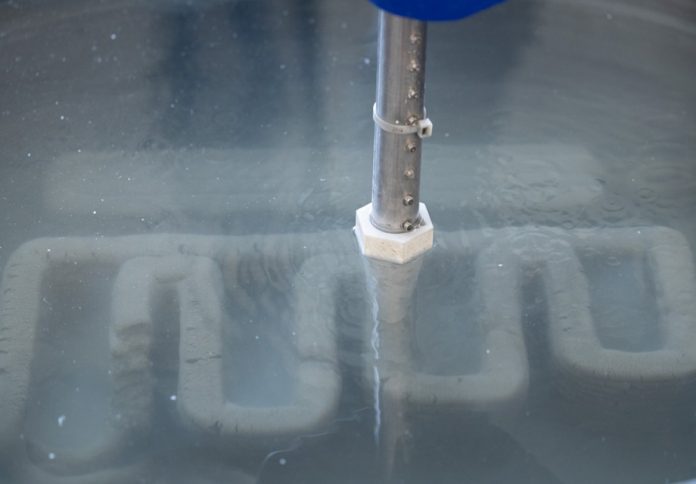

Nair said her group, which already had experience printing large-scale concrete structures on land, found that its material could be adapted for underwater use. “It turned out, with our mixture we could actually 3D-print underwater by making adjustments to account for continuous water exposure,” she said.

In May 2025, Cornell was awarded a one-year, USD 1.4 million DARPA grant, contingent on meeting specific technical benchmarks, with five other teams competing in parallel. One of the main technical hurdles is preventing “washout,” where cement particles disperse in water rather than binding together. “You’re balancing pumpability with these anti-washout agents,” Nair said, noting that shape retention and layer bonding are also critical challenges.

DARPA also required that the concrete be made primarily from seafloor sediment, reducing the need to transport cement by ship.

In September, the Cornell team said it demonstrated progress toward this target to visiting DARPA officials. “Nobody takes seafloor sediment and prints with it,” Nair said. “This is opening up a lot of opportunities for reimagining what concrete could look like.”

The project brings together expertise in materials, fabrication, robotics and sensing from Cornell and partner institutions.

Nils Napp, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, said monitoring the printing process underwater adds another layer of complexity. “Sediment is super fine, and as soon as you stir it up, you can have zero visibility,” he said, explaining why the team is developing sensor systems to track printing in real time.

The next phase of the DARPA challenge will conclude with a final underwater demonstration in March, where teams will attempt to 3D-print an arch structure.

Despite the accelerated timeline, researchers say the competition has driven rapid collaboration. “It’s a pretty ambitious timeline,” Napp said, “and it’s cool to see so many different areas of expertise coming together quickly and pushing this forward.”