As Australia’s shift to renewable energy gains pace, Monash University researchers are calling on the wind industry to use ecological data on seabird flight behaviour to help prevent wildlife collisions with offshore turbines.

The findings have been compiled into a practical guide aimed at supporting policymakers and renewable energy developers as Australia begins to assess environmental impacts for proposed offshore wind projects.

“The work we have done aims to constructively inform policy development at the intersection of biodiversity conservation and renewable energy; two areas inherently linked,” said Dr Mark Miller, lead author of the study and Research Fellow at Monash.

“This will help scientists and policymakers better understand and mitigate the risks of these unique seabirds colliding with offshore wind turbines.”

The Australian offshore wind sector is still in its early stages, with several companies currently navigating environmental assessments, including requirements to evaluate impacts on seabirds such as albatrosses.

Six offshore wind zones have been declared by the federal government, with feasibility licences now being considered. Licensees will still need to meet strict environmental standards and consult with local communities.

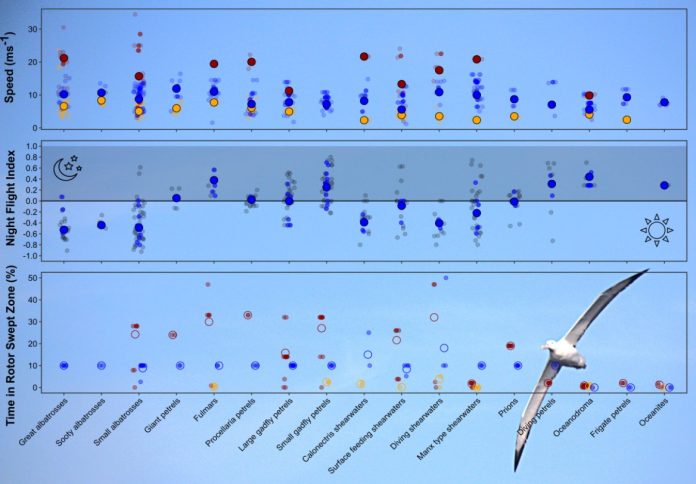

Dr Miller said that while the study draws on data from 119 seabird species to outline how high, how fast, and when seabirds fly, key knowledge gaps remain.

“One of these is that we currently have a poor understanding of seabird flight behaviour and how this might influence collision risks for iconic species such as albatrosses and petrels,” he said. “This is a crucial information gap, and one that should be a priority action for the offshore wind industry.”

He suggested that raising turbine heights could be a practical way to reduce the risk of bird collisions, noting that seabirds often fly close to the water surface.

Seabirds are among the most threatened bird groups globally, with populations declining by up to 70 per cent over the past 50 years.

Albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters and storm-petrels include both highly threatened and abundant species, making them central to conservation efforts.

Associate Professor Rohan Clarke, Head of the Research, Ecology and Conservation Group at Monash, emphasised the need for collaboration between ecologists and the wind industry. “Our job is to help deliver the best possible outcomes for biodiversity, and addressing climate change through large-scale action is essential to that goal,” he said.

He acknowledged the “green-green dilemma” where climate solutions can unintentionally cause ecological harm but insisted that addressing climate change must remain the top priority. “The energy transition isn’t optional, it’s essential, and finding solutions that support both climate goals and nature is critical.”

The full study is published in the Journal of Applied Ecology and can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.70088.