Researchers at Monash University say they have developed a new method to recover high-purity metals from spent lithium-ion batteries using a mild, environmentally sustainable solvent, offering what they describe as a safer alternative to conventional recycling techniques.

In a media release, the university said the process can recover nickel, cobalt, manganese and lithium from used batteries without relying on high temperatures or chemical-intensive treatments that are commonly used in existing recycling methods.

According to Monash, the approach addresses growing concerns about battery waste as global use of lithium-ion batteries continues to rise.

The university noted that an estimated 500,000 tonnes of spent lithium-ion batteries have already accumulated worldwide, while in Australia only about 10 per cent of spent batteries are fully recycled.

The remainder is often sent to landfill, where Monash said toxic substances can leach into soil and groundwater, potentially entering the food chain over time.

At the same time, Monash said spent batteries represent a significant secondary resource, containing strategic metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese, as well as copper, aluminium and graphite.

However, the university said current recovery methods are often limited in scope and efficiency, typically extracting only some materials and requiring hazardous chemicals or energy-intensive processes.

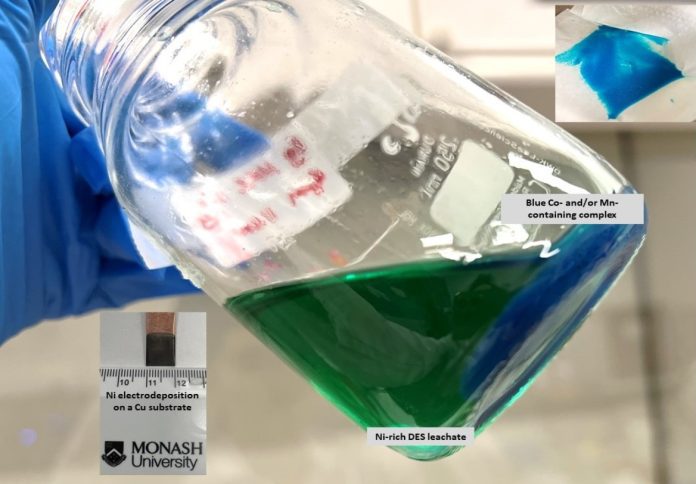

The Monash research team has developed a method that uses a novel deep eutectic solvent combined with an integrated chemical and electrochemical leaching process.

Dr Parama Chakraborty Banerjee, principal supervisor and project lead from the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, said the technique achieved high recovery rates even from complex industrial waste.

“This is the first report of selective recovery of high-purity Ni, Co, Mn, and Li from spent battery waste using a mild solvent,” Dr Banerjee said.

She added that the process was able to recover more than 95 per cent of these metals from industrial-grade “black mass”, which contains mixed battery chemistries and impurities such as graphite, aluminium and copper.

“Our process not only provides a safer, greener alternative for recycling lithium-ion batteries but also opens pathways to recover valuable metals from other electronic wastes and mine tailings,” Dr Banerjee said.

PhD student and co-author Parisa Biniaz said the research could support efforts to move towards a more circular economy for critical materials.

“Our integrated process allows high selectivity and recovery even from complex, mixed battery black mass,” Biniaz said.

“The research demonstrates a promising approach for industrial-scale recycling, recovering critical metals efficiently while minimising environmental harm.”

While the findings point to potential environmental and resource benefits, the university noted the work is based on laboratory-scale research.

Further development and assessment would be required before the process could be deployed at commercial scale.

The research has been published in the journal Sustainable Materials and Technologies.