One of the “hottest” metals currently garnering interest in additive manufacturing is copper – largely because of its greater thermal conductivity, which is desired in industries like electronics and rocketry where heat exchange is essential.

As such, common copper alloys for AM include GRCop-42 and GRCop-84 (both are copper chromium niobium), C18150 (copper, chromium, zirconium), C18200 (copper chromium), and GlidCop (copper and alumina).

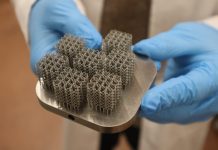

In an article written by Zachary Murphree, VP of Global Sales and Business Development at Velo3D, he stated that laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), or the manufacturing process that can deliver the extremely complex internal geometries being developed for the latest rocket combustion-chamber designs, or for cold-plate applications in electronics, made it possible for engineers to work with copper carried out in an airtight build chamber.

Major considerations in copper’s material qualities

The quality of the materials used is always the first step towards manufacturing high-value parts, and fusing copper with other metals to create the alloys required for 3D printing high-value parts has not been a simple feat. The majority of manufacturers of AM systems do not also atomise powders; instead, they rely on independent material suppliers to offer the raw materials their machines need in order to operate at peak efficiency.

Copper’s relative softness and stickiness, which make it challenging to blend with other elements, have presented challenges to those materials’ suppliers. For improved mechanical qualities, dispersion strengthening is used in some copper alloys.

For instance, when using GRCop-42, a crucible holding copper, chromium and niobium are heated above its melting point until the metals dissolve into the liquid copper. Chromium and niobium combine to form an intermetallic when the alloy is flash-frozen into an extremely fine powder.

The mechanical qualities of the material – strength, fatigue resistance, creep resistance -that reduce heat-flux (very hot on one side, extremely cold on the other) in the liner of a rocket thrust chamber are higher the smaller the intermetallic dispersion inside a powder particle.

According to Jamie Cleland, a materials expert with decades of R&D work in rocketry who’s now a California-based consultant, “You can’t get that key intermetallic formation of copper in an ingot; GrCop is only able to be manufactured as a powder. It was essentially a powder looking for a process, for years—before it found its niche in 3D printing.”

Cleland noted that Paul Gradl, a chief engineer at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Centre, is credited for pioneering the use of powdered copper alloys for AM.

Copper alloy gets certification from LPBF system providers

Gradl stated that switching from traditional manufacturing to additive manufacturing often resulted in cost reductions of more than 50 per cent and lead time reductions of up to 10 times. Convinced of the usefulness of copper for rockets, NASA persisted with GRCop-42, and today, after admittedly quite some time in R&D collaborations, it has succeeded in achieving its objective.

GRCop-42 and the more recent C-18150 have both been certified by several of the more advanced LPBF system vendors. Furthermore, trials for certification are being conducted on other copper alloys.

Persisting challenges with print accuracy and product integrity

Both AM machine builders and operators experienced more steep learning curves; dealing with copper presented particular difficulties for small contract manufacturers with limited experience, including print accuracy and product integrity problems.

As most LPBF systems use a fibre laser that works at near-infrared wavelengths, typically about 1070 nanometers, high reflectivity is a challenge that must be overcome. In order to start the melting process, these systems need even more powerful lasers, such as those in the 1kW range. Additionally, a copper-qualified printer must have a highly efficient cooling system built into its walls.

Stickiness also presents as an issue as copper alloys are relatively soft and gummy compared to other materials commonly used in AM. This can create issues in sieving, powder conveyance, and leftover powder removal after manufacturing.

Another problem is oxygen sensitivity. In the larger build chambers that are currently accessible, it is crucial to maintain a very low oxygen level. When working with copper, inert Argon gas is the preferred build-chamber medium.

“Once you know the tradeoffs of copper material, process control is clearly the key to success with printing with it,” says Cleland.

He added, “Layer-by-layer quality assurance checks that monitor hours- or days-long print are critical.”

Moving forward, data received from sensors during a build is used by process development teams at major AM system providers to fine-tune settings for working with more difficult materials like copper.