Graphite is a type of coal, crystallized carbon with a widespread use across many industries. It’s used for manufacturing pencils, batteries, electrodes, as a dry lubricant in machine parts, for making crucibles and so on.

But this is not the only reason why this material is considered very valuable. For all its virtues and applications, the biggest asset to gain from this mineral is graphene, a new wonder material that has the potential to transform a multitude of industries, from electronics to renewable energy.

In 2004, University of Manchester physicists Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov managed to do something that science deemed impossible. They figured out a way to isolate a sheet of graphene by simply stripping flakes of a block of graphite with sticky tape. Thus, the pair came up with micro flakes of a completely new material, its carbon atoms perfectly arranged in a dazzling honeycomb pattern.

“No one really thought [releasing graphene] was possible,” said the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. “Carbon, the basis of all known life on earth, has surprised us once again.”

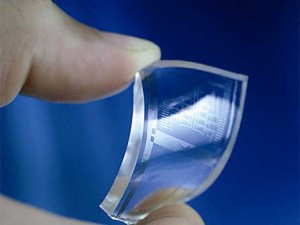

Graphene is the world’s thinnest material. It is incredibly flexible and 200 times stronger than steel. It is practically transparent, yet so dense, that not even the smallest gas atoms can penetrate it. On top of that, it is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity. While other materials such as silicon can emulate some of the properties of graphene, no material is able to boast such desirable qualities in one package.

“It’s beyond our comprehension of what is possible,” says Cathy Foley, Chief of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation’s Materials Science and Engineering Division when asked about the range of possibilities that graphene may open to science. “There will be changes that will blow us away.”

According to the article on the Sydney Morning Herald, researchers are fascinated by graphene’s potential for manufacturing biomedical tools, optics and plastic reinforcements (such as building lighter, hardier aircraft or satellites), as well as creating high-performance solar cells and electric vehicles and next-generation filters for water purification and desalination.

Such is the potential of graphene. No wonder major corporations such as Samsung are already racing to gain control of the market, while the European Union committed $1.5 billion to its multination research efforts last year.

Meanwhile, Australian researchers are toddling behind in the race for studying this wonder material.

“Our funding pool in Australia is much more limited,” says Dan Li, Monash University Professor who leads a team of ten.

“But that doesn’t mean we can’t do something unique. I wasn’t that optimistic about graphene at first,” he admits. “A lot of promising materials never make it to market.”

Australia has rather large graphite deposits, with several companies keen to begin mining operations.